Finding the Gethsemane in Garissa

By REV. CANON FRANCIS OMONDI

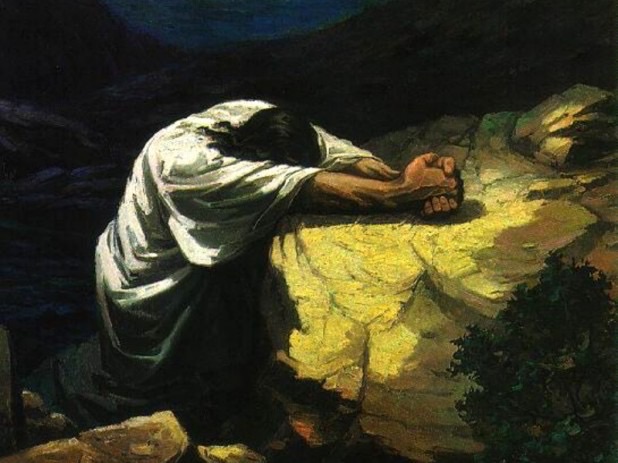

On the Maundy Thursday 2-APRIL-2015, Al-Shabaab – a Muslim terror group – woke the morning of Garissa University College with Terror. By 8 pm at the end of the Day of horror, more than 147 [govt count but witness claim 280-300] people were killed, either shot or slaughtered. The Christian Union group who had gathered for early morning prayers did not only lift their voice in prayers to heaven, the terrorist’s bullets lifted 13 of them up to the throne of the Lamb. They were brutally killed. The survivors and many of us Christians living in Garissa at the epicenter of terror attacks remembered Gethsemane.

He went away and prayed, “My Father, if this cannot pass unless I drink it, your will be done.” (Matthew 26:42 ESV).

We may not know nor can we fully comprehend either the physical or the spiritual pain that Jesus had to endure. Why would He make such a prayer? For up until this point, it seems that Jesus had known fully well what He would face on the cross, and went toward it willingly and resolutely. Both before and after the prayer in the Garden, Jesus knew what His death would entail, and showed complete acceptance of it. How, then, can we understand His prayer in the Garden for the cup to pass from Him?

Mathew [26:36] uses the Greek word parerchomai for pass, which could be translated in a variety of ways. It could speak about ‘coming to completion’, or ‘inability to pass away until it is fulfilled like in Matt 5:18. But we can benefit greatly from the Ginsburg Hebrew New Testament for insight to allow us appreciate Jesus’ prayer. Ginsburg, in Matthew 26:39, translated the word ‘pass’ in Hebrew as abar, which means ‘to pass through’. The import of his choice of words is visible from the account of the Passover (cf. Exodus 12:12, 23). Here, the Lord “passed over” (Heb. pesach) the houses of the Israelites marked with blood of the lamb on the doorpost, but He “passed through” (Heb. abar) the houses of the Egyptians without.

This fits perfectly with the Passover imagery. At Passover meal, they would have drunk deeply from four cups of wine. The custom was that when the communion cup came to the place you were reclining, you had to drink from it as deeply as you could, before passing it on to the next person at the table. Often, at the bottom of the cup, there were bitter dregs from the wine. If you were the person to empty the cup, you must drink the bitter dregs as well, before you “let this cup pass.”

So when Jesus prays, “Let this cup pass from me,” He is not saying, “I don’t want to drink it,” but is rather praying, “Let me drink of it as deeply as I possibly can before I pass it on to humanity. Let me empty it. Let me drain it. Let me drink all of it, even the bitter dregs at the bottom of the cup.”

Jesus’ shadow at the garden was cast over us. One can imagine the sweat drops of blood on his people in Garissa University. They now join many other Christians who have followed Christ in his agony. Philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaar rightly observed that, “Present-day Christendom really lives as if the situation were as follows: Christ is the great hero and benefactor who has once and for all secured salvation for us; now we must merely be happy and delighted with the innocent goods of earthly life and leave the rest to Him. But Christ is essentially the exemplar, that is we are to resemble Him, not merely profit from Him.” (The Journals of Søren Kierkegaard). The 13 Christian Union members gathered in prayers resembled him. Many who hid in the wardrobes and under their beds yet in fervent prayers were like him, resigned to God’s will. In our uncertainty, living in this context, we seek to resemble him in his agony of that night, all for our Redemption!

The terrorists’ false idea of linking non-Muslims with the government of Kenya contributed directly to the attack. There is a temptation, therefore, to engage in this matter from an increasingly complex religious political angle. It is clear that the students were killed due to the government’s policy on anti-terrorism. According to survivors interviewed, the Al Shabaab explained to students that they are paying for the mistakes and refusal of President Uhuru Kenyatta to withdraw Kenya Defence Forces from Somalia. This presents us with a dilemma of distinguishing whether this should be perceived as a religious persecution or a political one. But that they died because of their faith is explained in the way they were separated from their Muslim colleagues, none of whom were killed. There is some wisdom, though, in David Frankfurter, a College of Arts & Sciences professor and chair of religion, of Boston University. Frankfurter, whose expertise includes the religion-violence nexus, notes that: “One of the problems with discussing religious persecution is that in some religious traditions, persecution and martyrdom lie at the very heart of the stories that organize religious identity itself. We can observe this tradition in Judaism, Shiite Islam, and certainly Christianity, which begins with the martyrdom of an innocent man and continues with innumerable stories of graphic torture and death.”

How true that Christians embraced these stories, retold them, and even drew inspiration from them to annihilate perceived aggressors! Elizabeth Castelli, the Barnard scholar, has shown that persecution and martyrdom have offered Christians a sense of history, identity, community, and license for action. The great second-century Church father Ignatius of Antioch declared that only in persecution and martyrdom does Christianity become real, and most historians of the religion would say that this sentiment never really went away.

Terrorism is never an accident. It is deliberate, calculated, systematic and precisely executed. It has to be to succeed. But it needs soil in which to grow. That soil is a community that is prepared, consciously or unconsciously, to permit it, collude with it. In, The Prophet, it is said that “the leaf does not turn brown without the consent of the whole tree.” The resistance of Christian presence among Muslims has been cited as a case for terror.

Will the pressure of persecution on Christians curtail their witness? It is the will of God that all the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of God as the water cover the sea. In his prayers, Jesus says, “Yet not as I will, but as you will.” (Matthew 26:39, 42) He completely trusted God’s plan, and He knew God’s will would be done. Trusting God doesn’t mean that I will always understand suffering or the reason behind it. But I’ve learned that because Jesus trusted God, my life is forever changed.

F.W. Boreham made a most helpful observation on persecution and the spread of the Gospel in The Candle and the Bird, Boulevards of Paradise, when he noted: “If you extinguish a light, the act is final: you plunge the room into darkness without creating any illumination elsewhere….But if you startle a bird, the gentle creature flies away and sings its lovely song upon some other bough.” He wonderfully points out that death is not the snuffing out of a candle; it is the escape of a bird. There is a divine element in humankind—an element which no tomb can imprison. And, similarly, there is a divine element in the Church – an element that no persecuting fires can devour. What a joy to know that that the bird that has forsaken us – the saints slain by the terrorists’ bullets- is singing her lovely song, to somebody else’s rapture, on a distant bough.

Oh may they sing on until that day dawns for which the Church has ever prayed, and as Boreham eloquently puts it, “when the Holy Dove shall feel equally at home on every shore and the earth shall be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord as the waters cover the sea.” Jesus, as the Lamb of God slain before the foundations of the world, takes on the full brunt the punishment for sin and terror, allowing His blood to be put on the doorposts of all who believe in Him, so that punishment passes over them. It is God’s will that we drink from this cup also, lest we forget Gethsemane!

The writer serves with the All Saints Cathedral Diocese in Nairobi. The views expressed here are his own. (Caonoomondi08@gmail.com)