By Canon Francis Omondi (Ph. D).

Our democratic order manifests in a more pluralistic society, where freedoms in all areas of life have become even more valuable. Yet, whilst no right is absolute, the most basic freedom in a democratic society is religious freedom. The Constitution of Kenya 2010 guarantees freedom of religion, which can be enjoyed by individuals and religious associations or persons belonging to a religious community, in practising their faith. The Presidential Taskforce on the Review of Legal and Regulatory Framework Governing Religious Organisations in Kenya, which Rev Hon. Mutava Musimi chaired, promptly delivered recommendations, the regulating framework for religious organisations, just what President William Ruto wished for. From these recommendations, the government has crafted The Religious Organisations Bill 2024, to regulate religious practice in Kenya. I discuss the repercussions of imposing the proposed regulations on religious organisations. I opine that such censorship will impinge on the freedom of worship and is not in the interest of religious liberties.

What the bill proposed

The Presidential Taskforce Report observed religious organisations’ lack of transparency and accountability and assumed a gap in Kenya’s regulation framework for religious groups. It considered the Societies Act, incapable of addressing issues unique to the religious sector. So, it recommended a raft of changes to the law. Of these recommendations, and now adapted into the 2024 Bill, these two the Religious Affairs Commission and Religious Umbrella Organisations, might most undermine religious liberties Kenyans enjoyed.

First, the task force urged the government to establish the Religious Affairs Commission, to oversee religious institutions. The government in the Bill, created the office of the registrar of religious organisations, who shall in accordance with this Act, “issue, suspend or revoke certificates of registration” to religious organisations. With this authority given to register religious organisations, the officer shall sanction religious practices, banishing cults and extremist religions. In addition, the officer shall “enforce good governance in the management of religious organisations”.

Henceforth, the registrar determines the qualification of religious leaders and will “institute compulsory training for all leaders of religious organisations”. The registrar must “review and set qualifications of leaders of religious organisations registered under the organisation”. To register an organisation, “at least one religious leader with a degree, diploma or certificate in theology who may form part of the board of trustees”. Apart from meeting the registration demands of the register’s office, a group seeking state recognition must first get the approval and recommendation of an umbrella religious body.

Having registered a group, the registrar or umbrella religious organisation will conscript county officials to “carry out inspections of religious organisations operating only in their specific counties to ensure compliance with this Act”; and “supervise elections of members of the management structure of religious organisations operating only in their specific counties”.

Second, the task force recommended the creation of Umbrella Religious Organisations, under which all religious groups would operate. It envisaged a hybrid of self-regulation organisation with government involvement. The task force fashioned these umbrella organisations in the pattern of Public Service Vehicles (PSV) Matatu Sacco, where “…all Matatu owners to belong to a Sacco is something akin to what the religious organisations refer to as self-regulation”. The government controls Saccos operations through legislated laws and policies members implement. This self-regulation mechanism aspect impressed the task force, thus the desire to apply for religious organisations. This Bill will give the umbrella religious organisation powers to:

(a) [O]versee and regulate religious organisations registered under the organisation; call for information, or accounts; and (b) provide a forum for consultation among the religious organisations registered under the organisation; (c) develop theological training curricula and a code of conduct for religious leaders; (d) review and set qualifications of leaders of religious organisations registered under the organisation; (e) review doctrines and religious teachings of religious organisations registered under the organisation; (f) develop and implement guidelines on the activities of the religious organisations registered under the organisation; (g) establish an internal dispute resolution mechanism for its members.

Apart from peer-regulating religious groups, the umbrella bodies would tame deviant organisations and report their leaders to the government for abandoning agreed orthodoxy. So, the Bill places religious groups, like Matatus in a Saccos, under government-regulated umbrella organisations for registration and supervision during operation.

The Rationale for the Bill

President Ruto’s intent calling for “… the regulation of religious organisations, with the aim of stamping (sic) out rogue religious organisations and leaders” following the Shakahola ignominy was revealing. This task force might be like many other task forces and commissions in Kenya. Most commissions became government tools to cool down public outrage, a political strategy to defuse political and other tensions. And their output often aligned with the political purposes of those who appointed them.

However, in justifying these regulations, the Presidential Taskforce argued, “… public interest requires that there must be a healthy balance between the freedom of religion and the respect of the rule of law, respect for the rights and freedoms of others and general public safety and interest”. The task force claimed that rising “extremism behaviour and sprouting of otherwise non-anchored religious sects with uncensored teachings thrive”, because of the absence of a religious self-regulatory mechanism. It contended that the lack of a regulatory framework enabled incidents like Shakahola to occur.

The task force raised serious cases of human rights abuses, although not confined to the religious realm. Further, it claimed that religious institutions were non-compliant with the Societies Act, statutory requirements, so it proffered legislating special laws focused on religious organisations and crimes in religious contexts. These and non-compliance with statutory regulations must and could be addressed within our existing legal framework. Had the government enforced provisions in the Societies Act, instances like Shakahola would have been avoided. Shakahola was a criminal enterprise and neither religious nor spiritual adventure.

It is inexplicable that the task force failed to adopt the USA experience which they also visited. In the USA experiment, the government had no religious affiliations or tried the promotion of one. It rather affirms religious freedom while maintaining law and order. Whilst Freedom means that subject to such limitations as are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others, no one is to be forced to act contrary to his/her beliefs or conscience. Such an attempt by the state to regulate this freedom will cause disquietude.

How are we to understand Religion itself?

The Religious Organisation Bill compels us to rethink our characterisation of religion. The imperative to distinguish what religion means is pronounced in both classical Western and non-Western terms. This dialogue argues former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga, “is, indeed, the vision and the decree of the Constitution. In its secularity, the Constitution protects, defends, and upholds our freedom of religion and also our freedom from religion.” So, our understanding of religion has to be better thought through as we seek harmony in a plural religious context.

First, the task force, then the Bill, took a rather narrow view of religion, thus caging their categorisation of religious institutions. In defining a Religious Organisation as “An association, conference, congregation, convention, committee, or other entity organised and operated for a religious purpose”, the task force focused on the social at the expense of its spiritual aspect. Implicit in the term Religious is the spiritual, while Organisation is the social. The religious is innate, a given, which the government must only affirm, and the state does that through the constitutional provision of religious liberties. Whereas, the organisation is instituted, it is a social construct, and the same with other social groupings, the Societies Act establishes it.

Although the Religious Organisation Bill 2024 defines a religious organisation as “an organisation whose identity and mission is religious or spiritual in nature and which does not operate for profit”, how it describes it is devoid of the requisite spiritual accent. The Bill categorises religion in terms of organisations with a constitution, doctrinal statement, and sets of teachings. And it rates religious leaders as having formal degrees, diplomas, or certificates in theology. The Bill classifies religious organisations as corporate entities, with boards, trustees, committees, and whose output is in the number of adherents, account statements, assets field and a list of charitable activities in the society. This portrayal does not project religious organisations in their cultural and spiritual aspect. We, thus question with Richard J Schreiter, “Is ‘religion’ ultimately a Western or a Christian category?”

Would the baseline model of popular religion help reorganize our thoughts here? To conflate corporate characterisation for religious and formal theology for mystic revelation is to reduce religion to a view of life, forgetting that it is a way of life as well. This faith-religion distinction is a cultural distinction of the West, perhaps only of one form of Protestant Christianity. Religion cannot be reduced to a set of ideas as this Bill does.

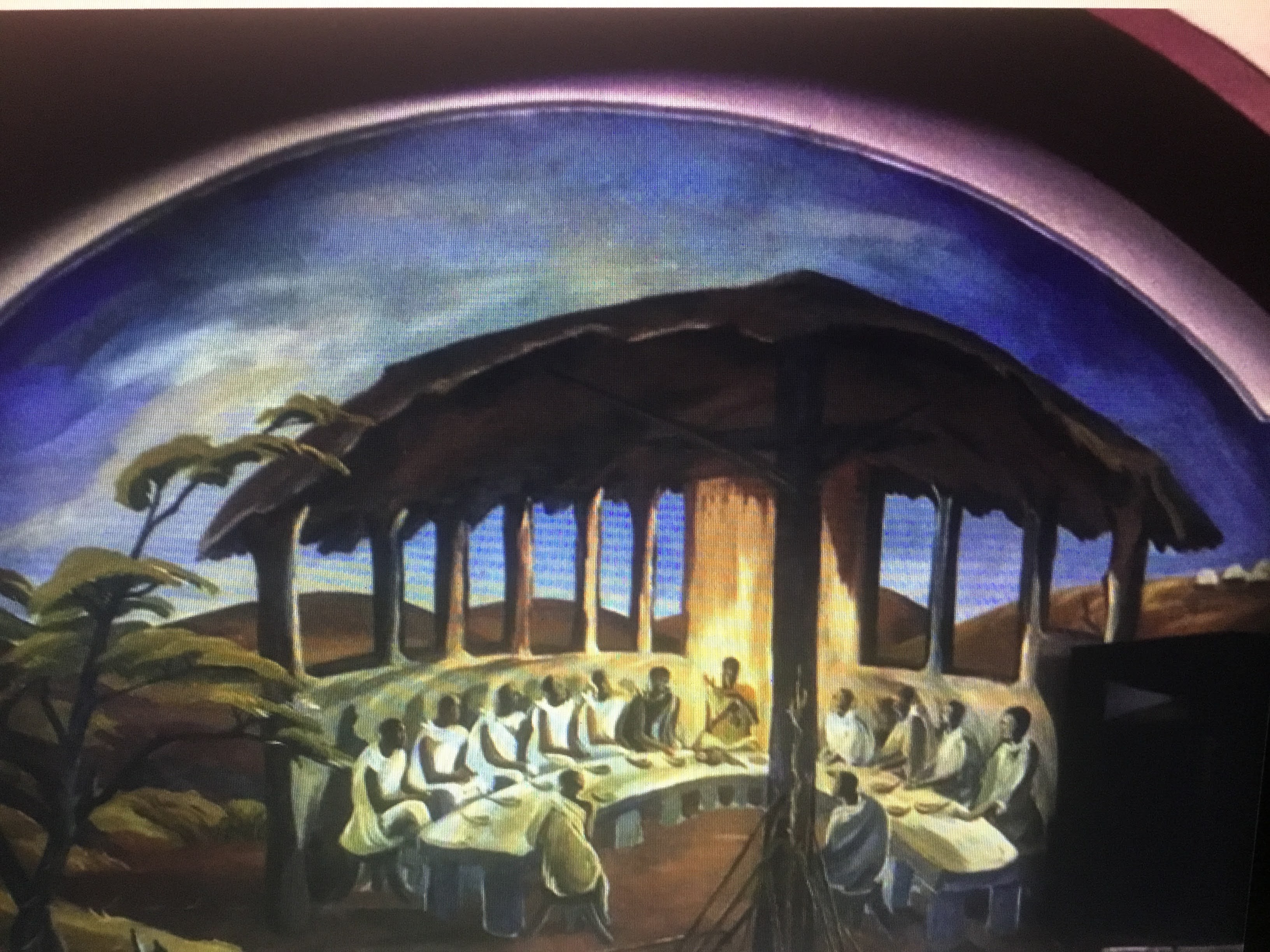

What “religion” means varies from culture to culture. Many African languages did not have a vocabulary for what we call “religion”, because religion is a way of being and living which, Schreiter further notes, is “so tied up with being part of a particular culture that it is impossible to imagine living that way outside the culture.” And when these groups adopted Christianity, aspects of the older understanding persisted since they did not see the new religion as replacing that way of living in the culture, but as enhancing it. The new faith expanded the old religions’ boundaries to the larger world, and in the words of Schreiter, “enhancing access to the sources of divine power, and providing better insight into what one has been doing already.” For this reason, it is not uncommon for some who adopted Christianity, to view it as a “religion” that adds something extra to their own, rather than something different.

So, what we regarded as a sect or cult, may have something to do with how one construes the limits of incorporating cultural elements into the new religion. Thus, before we render groups as cults or sects, we need to appreciate their pace and capacity to absorb foreign religious concepts, irrespective of whether they are Christian or Islamic. In addition, it may, according to Schreiter, have something to do with thinking about such choices disjunctively (as either-or) instead of conjunctively (as both-and)”. At some stage in Kenya’s history, spiritual cults were about freedom of religion. We need to be careful not to go back to the well-beaten path of calling certain beliefs satanic when they may be positive ATR values. The question to be raised again here is for whom are sects or cults and extremists a problem?

Enacting this Bill will forge all Kenyan religious groups in the mould of Western Christian religion. Kenyan worshipping in the Kaya of Kwale, the Mt Kenya forest, or on the shores of Lake Victoria, will now need to register members, write a constitution, publish accounts, register assets and document their doctrines. Their leaders will need to hold formal degrees or diplomas in theology. In African religions, it will be hard to distinguish clerics from community elders, since they also play the role of worship leadership. Our laws must accommodate groups like followers of Mary Senaida Dorcas Akatsa of Jerusalem Church of Christ in Kawangware, Nairobi. She draws thousands seeking healing and freedom from spiritual oppression. According to Prof Philomena Mwaura, of Kenyatta University, “Her healing ideology is derived from her indigenous Luhyia background. Mary retains the spiritual authority and is the patron of the church, while men have occupied legal authority.”

To comply with this Bill, Muslims may have to tinker with their religious practice to fit. Yet Islam is not confined to private life, hence remarkably different. Muslims understand Islam as a complete way of life. Religion guides all aspects of their lives – the individual and social, material and moral, economic and political, legal and cultural, and national and international. It is a misnomer applying Christian characterisations, “cleric”, to describe a Muslim scholar. Islam has no formal clergy, no ordaining body, and no hierarchy. In Islam, all strive to learn and do not specify who becomes a scholar. It is to these scholars that Muslim society turns to whenever they pray together. They select one individual to lead in prayers standing at the front of a congregation. The person, Imam, which means ‘the one who is leading’, is often the most knowledgeable of the Qur’an and Islam.

Instituting umbrella bodies as self-regulating religious groups will not only pressure religious organisations to conform to orthodoxy involuntarily but also put them under state control. This is the Bill’s most insidious demand. For it ensures the government keeps religious groups on a short leash. Classifying religious groups into umbrella groups will be a hard task. The difficulty will be more pronounced in Islam or African traditional religions, whose religious texture and association differ from Christianity. I wonder how the Catholic Church in Kenya will fit. Given its expanse, reach, history of going it alone and tradition, which umbrella group will it join? If exempted, will it not be obvious that this law targeted certain Christian religious groups? I hope the centring umbrella religious groups, such as NCCK, EFK, and AIC, were not a ploy to revive their waning fortunes.

Religious Organisation Bill’s effect on religious liberties

The Religious Organization Bill 2024 was casual and scant in guaranteeing religious liberties. In conferring unqualified authority to regulate the functions of religious organisations to the registrar, abuse is plausible. The registrar determines the qualifications and suitability of spiritual leaders, licencing the practice of religious groups and mediates in their conflicts. More worrying is this, the registrar has sole powers to “issue, suspend or revoke”, registrations. Vesting powers, to register and de-register a religious organisation on the registrar upon advice given by the umbrella religious organisation, allows the state an unfettered authority that might jeopardise freedom of association and religion. Because the state and its agents are now pivotal in adjudicating beliefs and religious rights.

Aware of the states’ inclination to usurp liberties, in the name of national security, drafters of the Kenya Anti-Terrorism Act of 2022 put caveats on the state’s authority. As a result, the Cabinet Secretary’s power to refuse applications for, and revoke the registration of associations of groups linked to terrorism needed the approval of the High Court. Consequently, the government may only revoke and refuse registration once the Court has determined and confirmed that the Cabinet Secretary’s order is reasonable. Being that the government did not unreasonably or for political victimisation or ulterior reasons, in seeking to limit association. Such legal proviso, where the judiciary determines the contours of religious liberties, best guarantees protecting freedoms of association.

The Religious Organization Bill 2024 focuses on censoring angular beliefs and religious organisations. However, letting the states have such a level of control would erode freedoms of belief. The essence of what is believed or worshipped may not be definite to any stringent logic or rationale, and applying the same standards to religious institutions may not be just. We may consider the point made by Justice Sachs J., of the South African Constitutional Court, that:

Religion is a matter of faith and belief. The beliefs that believers hold sacred and thus central to their religious faith may strike non-believers as bizarre, illogical or irrational… The believers should not be put to the proof of their beliefs or faith. For this reason, it is undesirable for courts to enter into the debate of whether a particular practice is central to a religion…

The umbrella organisation and registrar’s authority to sanction beliefs they consider extremists, sects, or cults might force individuals or groups’ beliefs to align with what the reasonable person (a non-believer) considers sensible. This may infringe on the core of religious liberty. Beliefs are subjective and founded on faith. We should not base freedom of religion on the rules set by the state and its agents but on the inherent dignity and the inviolable rights of the human person. Clarifying this concept, Justice Dickson C J., of the Canadian Supreme Court, ruled:

“The essence of the concept of Freedom of Religion is the right to entertain such religious beliefs as a person chooses, the right to declare religious beliefs openly and without fear of hindrance or reprisal, and the right to manifest religious belief by worship and practice or by teaching and dissemination.”

But the concept of freedom means more than that.

We can characterise this freedom through the absence of coercion or constraint. As the Canadian Supreme Court ruled, “If a person is compelled by the state or the will of another to a course of action or inaction which he would not otherwise have chosen, he is not acting of his own volition, and he cannot be said to be truly free”. Further, this Court listed forms of coercion as either direct, to include compulsion “to act or refrain from acting on pain of sanction and indirect seen in controls determining or limiting alternative courses of conduct available”.

So, instituting regulatory umbrella bodies to coerce individual religious groups into conforming to their doctrines to allow beliefs to be registered undermines their right to manifest, change and practice beliefs. Freedom embraces the absence of such coercion or constraint. Christianity is unsettled, marked by breaking out from the oppressive old and forming new outfits. Marie Perin-Jassay observed, this pattern among women of Kenya’s Legio Maria, how women found “The duties and tensions of the home, from the domination of men over women, from the burdens of traditional customs and innumerable taboos, from the threat of death and disease of their children. Liberation in faith from everything that oppressed them, until a source of power stronger than the traditional sources, ancestors, spirits and magicians, had offered them: Christianity, in which all human beings regardless of age or sex could reach God.”

Beliefs, contends John Rawls in Political Liberalism, are matters of conscience, thus personal and subjective. Whenever governments purport to grant freedom of religion, they often qualify the extent freedom is exercised by imposing state-recognised religion or elevating the state’s national interests over individual rights. Note that rulers categorize their class interests as national! What national interest is, has to be interrogated. Our government must refuse to impose on citizens any religious ideology unduly checking freedom to practice religion.

Given Kenyan religious and ethnic divides, the registrar of religious organisations’ reliance on county officials to conduct inspections and ensure operational compliance of religious organisations in their specific counties may lead to persecution of religious minorities in certain counties. How do we safeguard religious minorities from the threat of “the tyranny of the majority”? Because what may appear good and true to a majority religious group may be imposed upon minority religious citizens resident in certain sections of the country. This may be accentuated when the majority religious group acts at the state’s behest the state to reign in groups taking a contrary view.

If the fundamental religious liberties, including those of minorities, should be respected and not limited, a different adjudicator, other than the state operatives, is needed. One to deal with disputes in a nuanced and context-sensitive form, our judiciary. It is a judiciary conduct to draw boundaries and determine the limit of religious rights. The courts, not the state or these quasi-state bodies, must be the arbiters. However, Justice Mutunga cautions, “The judiciary authority is anchored to the vision of the Constitution which frowns on individuals and institutions playing God. Freedom of religion is only limited if it is criminal… there is a wealth of legislation on crimes committed by organizations and individuals.” Judges are not prophets, and the Constitution is not a “holy book”.

What is the point of making it so difficult for religious groups to operate in Kenya? Why deliberately crush constitutional liberties to cure a misdiagnosed social disease?

Religion, with its implicit freedom, is a “moral force” in a society that we must not unduly fetter.